Evanston RoundTable, May 12, 2022

Over the last 250 years there have been many musical geniuses, from Bach to McCartney. But none could do all the things he has done.

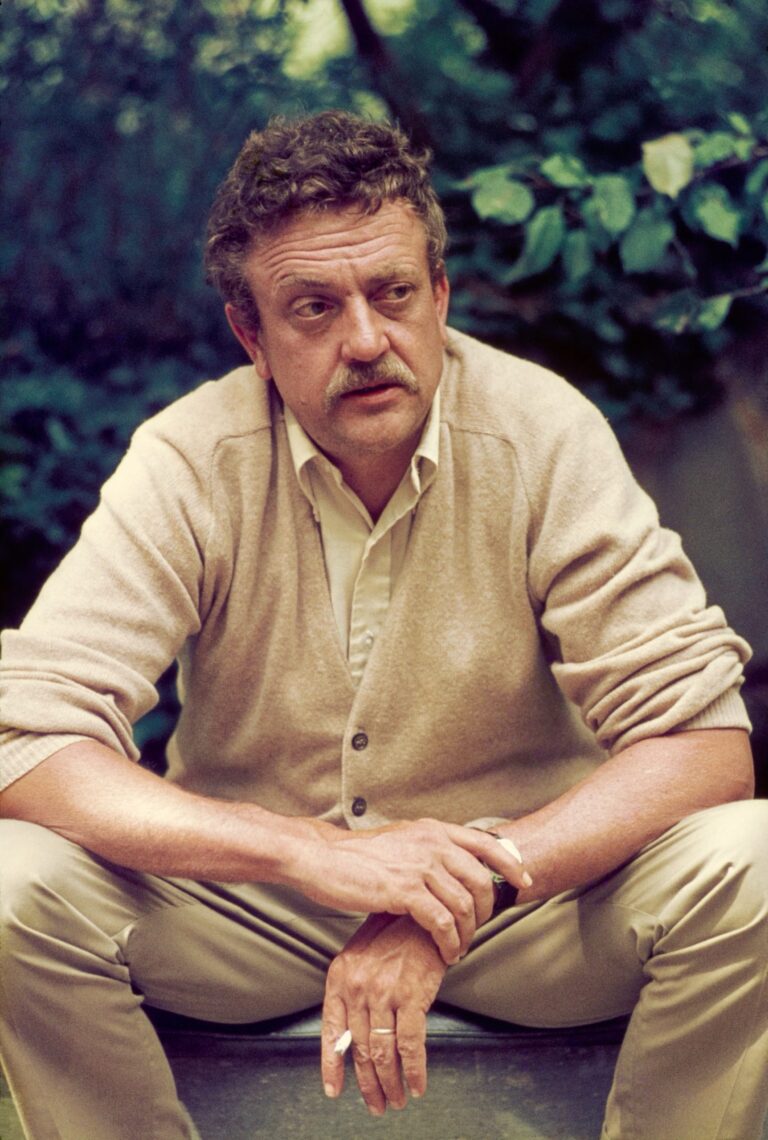

May 12 is Steve Winwood’s 74th birthday, making today the perfect day to celebrate the British music icon’s unique talents as composer, producer, arranger, singer and multi-instrumentalist.

But despite his Grammy and Jammy and BMI Icon awards, his three honorary doctorates, his 22 studio albums plus numerous live and best-of compilation recordings and more than 130 songs, many of which are classics, his appearances with musicians ranging from Billy Joel and George Harrison to Jimi Hendrix, Carlos Santana, Eric Clapton and Prince, his compositional chops and songwriting genius – admit it, you’re thinking: why should I care?

Beethoven complained of that kind of neglect, too, at the end of his career, and Bach’s music was ignored for three generations after his death.

So let’s rectify your ignorance of Stephen Lawrence Winwood right now! Herewith a number of my favorite compositions that hopefully will give you some appreciation – new or renewed – for his genius.

More than half a century ago this was the gateway song that first led me to his music, for which I still have an insane attachment. It’s an obscure but deliciously upbeat little number from 1968:

Who Knows What Tomorrow May Bring

Just three minutes long, there’s plenty to admire. First is Winwood’s rich vocals with its two-octave range, from tenor falsetto to bass, and his wonderfully jazzy organ playing. There’s his overdubbed bass and lead guitar lines. Then there’s the song’s classical structure, built on ascending and descending semi-tones and repeated three-note beats. There’s the seamless chord changes and organ playing that combines the bluesiness of American soul master Jimmy Smith with the melodic richness of Franz Schubert.

At the other end of the spectrum is Night Train from 1980, a fiery Concerto in D Minor for Guitar, Keyboards and Vocals, in which, astonishingly, Winwood performs every instrument. Goofy video notwithstanding, it is a tour de force performance that has to be seen to be believed.

And somewhere in between is this plaintive mid-tempo number from his first solo album released in 1977, with sinuous synth lines, beautifully measured intervals of seconds and fifths and a lovely guitar solo (a la Miles Davis) at the fade on “Hold On.”

Winwood grew up in Birmingham, England, a prodigy in a family of musicians. At nine he played piano in his father’s jazz band and as a teen was backing visiting American blues icons such as Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker and Sonny Boy Williamson. Around the same time, he was “discovered” by Birmingham bandleader Spencer Davis, who later said he was astonished to find “this kid playing piano like Oscar Peterson and singing like Ray Charles.”

Davis wasn’t the only one. On his 1965 English tour Bob Dylan expressed amazement at Winwood’s preternaturally soulful voice, and Dylan’s pianist Al Kooper described him in a 1968 Rolling Stone article as a “calm, shy superfreak,” a musical force of nature.

Spencer Davis Group and Traffic

With the Spencer Davis Group, the young Winwood showed why: he sang lead vocals and played keyboards and guitar on their four studio albums, knocking the Beatles off the top of the English pop charts with this spirited Jackie Edwards’ number in 1966. A year later Winwood wrote the SDG’s breakout hit, Gimme Some Lovin.’ On this clip, filmed live in 1967 on Finnish TV, you can hear the teenage Winwood’s hair-raising vocals and fiery Hammond B3 organ. This YouTube comment got it right: “The SOUL in his voice, and at such a young age he had so much vocal power. Seventeen years old, what a legend this man.” (Here’s a 2020 version demonstrating his pipes and organ chops are still wholly intact.) Another Winwood hit for the Spencer Davis Group, their last, was I’m a Man, captured live in a torrid big band session for VH-1 television in 1997. Note the razor-sharp rhythms to which you could set an atomic clock and Winwood’s Hammond solo starting at 1:35.

On the eve of SDG’s first American tour, Winwood quit the band, explaining simply, “I didn’t want to continue playing and singing songs that were derivative of American R&B.” In its wake he formed Traffic, a four-piece progressive rock ensemble that with overdubbing could sound like a small orchestra. Winwood played piano, organ, harpsichord and lead, rhythm and bass guitars; Chris Wood handled tenor sax, flute and occasional keyboards; Dave Mason performed on guitar and sitar; and lyricist Jim Capaldi banged away on the drum kit and other percussion instruments.

The band decamped from London to Berkshire, where they settled into a rural cottage to write and arrange the songs that ultimately appeared on Traffic’s first three albums. And what songs they were. There’s the haunting No Face, No Name, No Number; the Winwood showpiece Shanghai Noodle Factory (another personal fave) with overdubbed vocals, organ, and acoustic and bass guitars; and the wonderfully eerie 40,000 Headmen, a three-minute art song on a par with Schubert or Shostakovich. Aside from writing the music, Winwood sang the powerful vocals and laid down the bass and rhythm guitar and Hammond organ parts, something Schubert and Shostakovich could certainly never have pulled off!

Traffic was one of the pivotal progressive rock bands of that golden era. They recorded seven studio and two live albums over seven years – all unique, all standouts. They toured extensively throughout Europe and North America, first appearing in Chicago at the Aragon Ballroom in June 1970. (In a 1968 Traffic performance in Budapest, Winwood dedicated Who Knows What Tomorrow May Bring to the Communist security police, which frightened and thrilled the audience and inspired a young Andras Simonyi, later to become Hungarian Ambassador to the U.S., to award him the Golden Eagle medal. The incident is described in Simonyi’s book, Rocking Toward a Free World: When the Stratocaster Beat the Kalashnikov.)

With Traffic and in his later solo music, the classically trained Winwood could write songs in almost compositional style, utilizing intervallic relations like the exuberant octave leaps in his lilting 1982 pop song Valerie.

Traffic broke up in 1969 and Winwood formed Blind Faith with legendary rock guitarist Eric Clapton. They made only one album, a highlight of which is the masterful Winwood ballad Can’t Find My Way Home.(Here’s a more recent, solo recording from his home studio in Gloucestershire.)

Winwood reformed Traffic in 1970 and recorded the epic John Barleycorn Must Die album, which contains the definitive version of the magnificent Elizabethan folk song celebrating the tenacity of the barley from which beer is made. (Here’s a wonderful live clip, again filmed in his home studio.) The album’s opening two songs, the instrumental Glad, featuring Winwood’s jazz-infused piano and the buoyant rocker Freedom Rider, connected by a minor key bridge, comprise a 12-minute piece de resistance, a three-movement symphonic suite. In his usual Renaissance manner, Winwood wrote and sang the music, and played bass and lead guitar and piano and organ. (Producer Russ Titelman later marveled at how, in the studio, Winwood moved serenely from one instrument to another to lay down his exquisite tracks.)

Traffic’s 1971 album Low Spark of High Heeled Boys contains one of their great masterpieces, the iconic jazz rock song of the same name. The piece runs an epic 11 minutes and features Wood’s outstanding sax and Winwood’s monster keyboards and vocal mastery.

Except for a 1994 reunion album (which they performed opening for the Grateful Dead at Soldier Field that summer), Traffic finished up in 1972, ushering in Winwood’s solo career. Here’s the classic While You See a Chance from 1980. Later in the decade he was nominated for eight Grammy awards (and won two) for his “comeback” albums Back in the High Life and Roll With It. My favorite songs from that period are the glorious The Finer Things, the buoyant Shining Song, the soulful Holding On with its deeply spiritual second verse starting at 2:30 and the delightful back-to-roots hottie Roll With It.

From his penultimate 2003 masterpiece About Time comes the brilliant Different Light with Winwood on a wonderfully jazzy Hammond organ and foot-pedal bass and the Latin-influenced Domingo Morning.

And on his last studio album, Nine Lives from 2008 is Hungry Man, a complex five-part song that swings between major and minor keys interweaving polyphonic sections like a Bach cantata.

Classic live recordings

To see Winwood in person is one of the great joys of concert-going. Alas, he has withdrawn from this summer’s Steely Dan tour, presumably over COVID concerns. But if you get the chance somewhere, sometime – go.

Here are a few favorite online clips. One of the all-time great live performances is George Harrison’s classic While My Guitar Gently Weeps from the 2004 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony that features Prince’s legendary guitar solo at the end. Winwood accompanies on Hammond organ.

Winwood recorded Voodoo Chile with Jimi Hendrix in 1969 on the classic Electric Ladyland album, and while the Hendrix estate doesn’t permit the monster blues jam on YouTube, here’s a great version with Winwood and Clapton.

Invited to sit in with the legendary Motown rhythm section The Funk Brothers, Winwood blew the roof off the Hamburg hall in 2004 with this spirited version of Junior Walker’s R&B classic Shotgun. And a bonus at the end: you can hear his lovely tribute to “such fantastic musicians…it’s a real pleasure and a real honor, for me.”

Here’s a wonderful live clip of Roll With It with a splendid big-band horn section. And from the same 1989 concert, a beautiful rendition of his Grammy-winning Back in the High Life performing on mandolin.

Perhaps my favorite live recording is Winwood singing another R&B classic, Road Runner, from the 1983 Arms all-star concert in London featuring Clapton on guitar and the Rolling Stones’ Charlie Watts on drums. The 1980s-era synthesizer sounds cheesy to our contemporary ears, but hear how gloriously he makes it sound with his three short solos, especially the last one starting at 2:25 (catch the long high C at the end) during which Clapton fingers delicious guitar fills. Amazing!

Winwood and Clapton palled around in London as teens, as you can hear on the blues classic Crossroads from 1966. That’s Clapton on red-hot blues guitar and an 18-year-old Winwood on raw vocals. The song was written by the iconic Delta bluesman Robert Johnson, who legend has it made a compact with the devil to produce his unearthly guitar and vocals. Is it any wonder Winwood sings the part with such boyish glee?

And this last clip, a song he wrote for his good friend Christine McVie, Ask Anybody, featuring the Fleetwood Mac chanteuse’s wonderful vocals and Winwood performing magnificent solos on the keyboard synthesizer.

A few end notes. Winwood rarely wrote his own lyrics, and the words he does sing almost never rises to the level of “art.” His music – the great songs, the golden voice – was and is his legacy.

Will he record again? Tour again? No one knows. All he will say is that he is “semi-retired,” which could mean anything.

Curious readers might be led to ask: if Winwood is so iconic, why isn’t he better known and celebrated? Several answers: his music defies categorization, it doesn’t fit into any easy slot. And his gift for melody runs counter to the current funk/rap ethos, which is all about rhythm. Beside that, he has never cared for and in fact has always shied away from publicity and self-promotion. Again: it was always about the music.

And what music! The above two dozen songs could easily be swapped out for dozens of other Winwood classics.

Over the last 250 years there been many musical geniuses – Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, and in the last century Louis Armstrong, Cole Porter, George Gershwin, Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Duke Ellington, Leonard Bernstein, Benny Goodman, Stephen Sondheim, Nina Simone, Stevie Wonder, Paul McCartney and scores of others. But none of them – not one – could do all the things Winwood has done.

+ There are no comments

Add yours