Evanston RoundTable, March 28, 2024

Can’t say I’ve hung out with too many icons. As a kid, I was introduced to Wilt Chamberlain in the bowels of the Philadelphia Arena where the Warriors played. I remember having to reach straight up to shake hands with the basketball giant.

I tried to get Willie Mays’ autograph at the old Polo Grounds. He was signing scorecards before a Giants game at the railing near first base, but walked off (in disgust?) after I started hectoring: “Hey Willie, over here!”

I saw Martin Luther King Jr. twice, once in July 1966 at Soldier Field, the second time nine months later at the U.N. Plaza in one of his first major speeches against the Vietnam War.

I shook Robert Kennedy’s hand at a 1967 Chicago campaign event and got shooed away by Ald. Roman Pucinski, a party stalwart, for waving a homemade sign that read “RFK not LBJ in ’68!”

In November 1970, when I showed up uninvited at the door of his Cotswolds manor, the great Steve Winwood invited me in and served me Earl Grey tea. We talked about Hendrix.

I was at a 2013 book signing in Kenwood with then-Senator Obama, who remembered my son-in-law from a campaign event a year earlier.

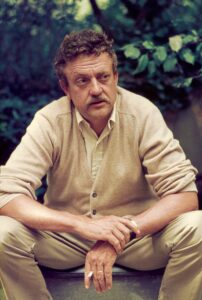

But as memorable as these experiences were, they pale in comparison to the weekend I spent with Kurt Vonnegut.

The famed author came to Chicago on Saturday, Sept. 28, 1996, as the guest of Steppenwolf Theatre, which was dramatizing Slaughterhouse-Five.

Aside from the play, the story (based on Vonnegut’s own experience as a German POW), was also made into an opera and a movie. It’s been translated into more than 20 languages and is listed No. 18 in the top 100 novels of the 20th century by Modern Library.

At the performance the next night, a string ensemble was scheduled to play excerpts from Shostakovich’s amazing Eighth Quartet, the subtext of which was the bombing of Dresden (where the quartet was written) that was the focus of the book. There are moments in the quartet when the strings blast out the sforzandosound of the bombs. (You can hear them 24 times starting at 12:38 in this performance.)

The quartet is dedicated to “the victims of fascism and the war.” According to Wikipedia, Shostakovich’s son Maxim said that was a reference to the victims of all totalitarianism; his daughter Galina said the composer was actually dedicating it to himself, a victim of Stalin’s repression.

I was working on a play about Shostakovich (still am, unfortunately), featuring a great deal of his music as an artistic gateway into the life and times of Stalin’s Russia, and had called Steppenwolf asking if I might meet the renowned author. Maybe he could shed some light on the composer, one icon reflecting on another. The request was fairly audacious and I expected a swift rebuff. But no, they told me he was meeting some faculty and students at Northwestern Saturday afternoon, and was scheduled to have dinner with them at Tommy Nevins Pub on Sherman Avenue. Would I be able to join him there?

Cool!

When I arrived Vonnegut was holding court in the back, carousing with the students and inviting strangers (like myself) to join the ever-expanding group. He smoked and drank prodigiously, laughed raucously and talked with everyone. When I was able to get a word with him, I asked if we could discuss Shostakovich.

Sure, he said. Why don’t you join me in the Green Room before the performance at the theater tomorrow night? We can chat there.

So of course I did.

Prior to the performance there was a question-and-answer session with Vonnegut. The author commended the design of the set, which he said looked like “where we lived in Dresden, in a slaughterhouse [underground], a cement block meat locker to house pigs.” But at that point in the war, “Germany was out of pigs, so they put us there.”

He said he and his fellow prisoners could hear the horrific firebombing of Dresden Feb. 13-15, 1945, thought to be one of the largest massacres in human history, killing an estimated 135,000 people, according to Vonnegut. (Contemporary estimates are far lower.)

“I was there, I’m entitled,” he said of his decision to cast the horror into fiction.

He said when the prisoners finally emerged aboveground, “everyone else for miles around was dead.” The men were dispatched to dig up corpses and set them alight on huge pyres. “That made you think about death.”

The model for Billy Pilgrim, the book’s central character, was a fellow soldier of Vonnegut’s named Edward Crone, who died a POW in Dresden. After the war his parents had him re-interred in their hometown of Rochester, N.Y.

Vonnegut said he visited Crone’s grave in 1995, while lecturing in Rochester. “That closed out the war for me. He [Crone] gave up, because life made absolutely no sense to him. And he was right, it wasn’t making any sense at all,” Vonnegut told the audience with a wry laugh. “He didn’t want to pretend he understood it anymore, which is what the rest of us did – pretend that we understood it.”

Notwithstanding the insanity of the war, Vonnegut admitted, “I wouldn’t have missed it for the world. It was a hell of an adventure. As long as you’re going to see something,” he chuckled, “see something really thought-provoking.”

Vonnegut related that in 1995 he spoke at a 50th anniversary memorial service of the bombing of Hiroshima, held at the University of Chicago, site of the first controlled nuclear reaction that led to the Manhattan Project and ushered in the nuclear era. Someone asked whether the U.S. should have bombed Hiroshima.

“I said I had to honor the opinion of my friend William Styron, who was a Marine in the Pacific. … He said thank God for the atom bomb on Hiroshima or I’d be dead now, because he was in training for the landing.” Vonnegut laughingly pointed out that Styron made the statement on a visit to Japan.

But Vonnegut said he disagreed with the bombing of Nagasaki. “It was utterly uncivilized and cruel … That was just for the hell of it, because certainly the military point had been made.”

The emcee asked, “And so it goes?” and Vonnegut echoed, “Yeah, and so it goes.”

After the Q&A session and before the evening’s performance, I was shown into the Green Room, where I was astonished to see we were the only people there. How incredible! Alone with the great author, like hanging out with George Elliot or Jane Austen! He was as welcoming as the night before. I told him I had recently reread Slaughterhouse, and of course enjoyed it. But there was just this one thing.

Oh? What was that?

I told him I counted 104 instances where he used the phrase, “And so it goes.” I didn’t ask him what it meant, or why he repeated it so many times. Was it a cosmic shrug of the shoulders about life? A plaintive shake of the head about the senselessness of war? A spit in the wind regarding God’s indifference to humanity? I thought it was too forward to ask directly, so I just let the statement hang in the air, like a bubble, hoping he’d respond.

He didn’t. He just looked at me pleasantly, and the bubble floated away.

OK.

I asked him about Shostakovich. Had he read up on him? Listened to his music? Thought about the great composer’s courageous resistance to Stalin’s murderous stranglehold on artistic expression? It had the makings of a Vonnegut novel. (Or a great play.)

No, he admitted. Didn’t know a thing.

OK.

I rose to shake his hand and thank him for his time.

“If you have any questions, don’t hesitate to call me,” he urged. “My number is pretty hard to forget: 212-MUTANT-1.”

Maybe he was pulling my leg, though for some reason I never for a second doubted him. But I never did call. What more was there to ask?

Postscript: Longtime Evanstonian Tim Evans, executive director of Northlight Theatre, was producer of the Steppenwolf Traffic series that staged the Slaughterhouse-Five performance that night 27 years ago at which Vonnegut appeared. “He was the nicest guy,” Evans said.

For a forthcoming column I’d be interested in hearing from anyone challenged by the purgatory of dealing with multiple passwords. Please email me at lesterjake@comcast.net.

+ There are no comments

Add yours