Evanston RoundTable, Jan. 25, 2024

I always imagined, growing up, that enlightenment would come to me (and everyone else) with age. By enlightenment I mean the understanding and appreciation of the true essence of things, the deep insights into the real and inherent nature of the world, as if a vast wind had swept in and cleansed the dust and haze from our vision and mind. Life and meaning would all grow clearer over time, granting us the perfect translucence of the air after rain, the “spotless mirror” of Buddhist teaching.

Because let’s face it – life is anything but clear to the unenlightened, which is most of us.

Well into my eighth decade (and not so much because I’ve suddenly become enlightened), I think I have finally discovered the essence of life.

It is, in a word, sadness.

Sadness at pain, sadness at suffering, sadness at evil, war, killing, discord, as well as the inevitable path to decline and death, and possibly the worst of all, the loss of parents and older siblings as well as dear friends.

I say this with great reluctance and regret, since I am innately an optimistic person. I’m so glass half full I don’t even see the glass half empty.

I’ve always argued things were better than they seemed, that life wasn’t as troubling as it appears in headlines and news broadcasts. (Darn that pesky news media!)

And that’s certainly true if you take a long enough view. In a 2016 article the website Vox listed six important areas of vast human improvement, mostly in the last two centuries:

- Declining poverty: “In 1820, only a tiny elite enjoyed higher standards of living, while the vast majority of people lived in conditions that we would call extreme poverty today. Since then, the share of extremely poor people fell continually.”

- Increased literacy: “In the past, only a tiny elite was able to read and write. Today’s education – including in today’s richest countries – is again a very recent achievement. It was in the past two centuries that literacy became the norm for the entire population.”

- Improved health: “In 1800, the health conditions of our ancestors were such that around 43% of the world’s newborns died before their fifth birthday.”

- More freedom: “Throughout the 19th century, more than a third of the population lived in colonial regimes, and almost everyone else lived in autocratically ruled countries … now more than every second person in the world lives in a democracy. The huge majority of those living in an autocracy – four out of five of those who live in an authoritarian regime – live in one country, China.”

- Population trends: “In pre-modern times, fertility was high – five or six children per woman was the norm. What kept the population growth low was the very high rate at which people died …. The increase of the world population followed when humanity started to win the fight against death. Global life expectancy doubledjust over the past 100 years.”

- Greater education: “The younger cohort today is much better educatedthan the older cohorts. And as the cohort size is decreasing, schools that are already in place can provide better for the next generation.”

That is all well and good – wonderful, in fact.

The problem is that we don’t live life in the long view; we live in the here and now, a place beset by the troubling trends of modern life. Anyone with an iota of awareness has to acknowledge the pain, confusion and suffering in the world.

Knowing this, how can one endure life?

A native Evanstonian happens to be an expert on these matters. Charles Johnson, about whom I’ve written before, and still earlier here, was born in Evanston’s Community Hospital in 1948 (“on Shakespeare’s birthday,” he likes to say) and graduated from Evanston Township High School in 1966. He went on to become a renowned novelist, winner of the 1990 National Book Award for the novel Middle Passage, a MacArthur Genius Fellow and an expert on Buddhism and eastern philosophy, about which he has written many books and articles.

Buddhism teaches us that suffering is universal and inevitable, but there is a remedy. When I wrote Johnson recently to inquire about this remedy, as well as the difference between sadness and suffering (close cousins in my book), this was his response:

“There’s an often-used saying by Buddhists I know: ‘Pain is something that comes in life, but suffering is voluntary or optional.’

“I would say the feeling of sadness is suffering, but I would add that as a feeling it is impermanent, as everything in this universe is (including the universe itself). It will appear, rise, then fall away if one does not cling to it. You don’t need to eliminate the painful feeling. It’s best to experience it fully, know you are not this feeling, that feeling and thoughts metaphorically arise – it’s what the mind does, it generates thoughts and feelings.

“So be with the fleeting feeling of sadness when it arises. Face it. Becomes friends with it, but not attached to it. Then let it go its way, as it will.”

Johnson also directed me to his essay in the 2022 graphic novel The Eightfold Path that he co-authored with Steven Barnes, which describes the Precepts he adheres to in his own Zen practice. They include “[be] generous [and] do not give way to anger,” among other do’s and don’ts. The Precepts, he writes, “… are not rules or commandments, only guides for achieving happiness and freedom from suffering. As such, they require a new and imaginative application of the Precepts and Eightfold Path each day as we try to lead the most examined life possible. This has always been the most creative of human projects, like painting a canvas with every one of our thoughts and deeds, since every moment of one’s life is new and like no other. The final painting, a masterpiece, will be your life itself.”

The great Buddhist peace activist and writer Thich Nhat Hanh wrote in The Heart of the Buddha’s Teaching that “The ocean of suffering is immense but if you turn around, you can see land.”

Several other antidotes to sadness, less profound but perhaps more accessible, come to mind – all as it happens starting with the letter L.

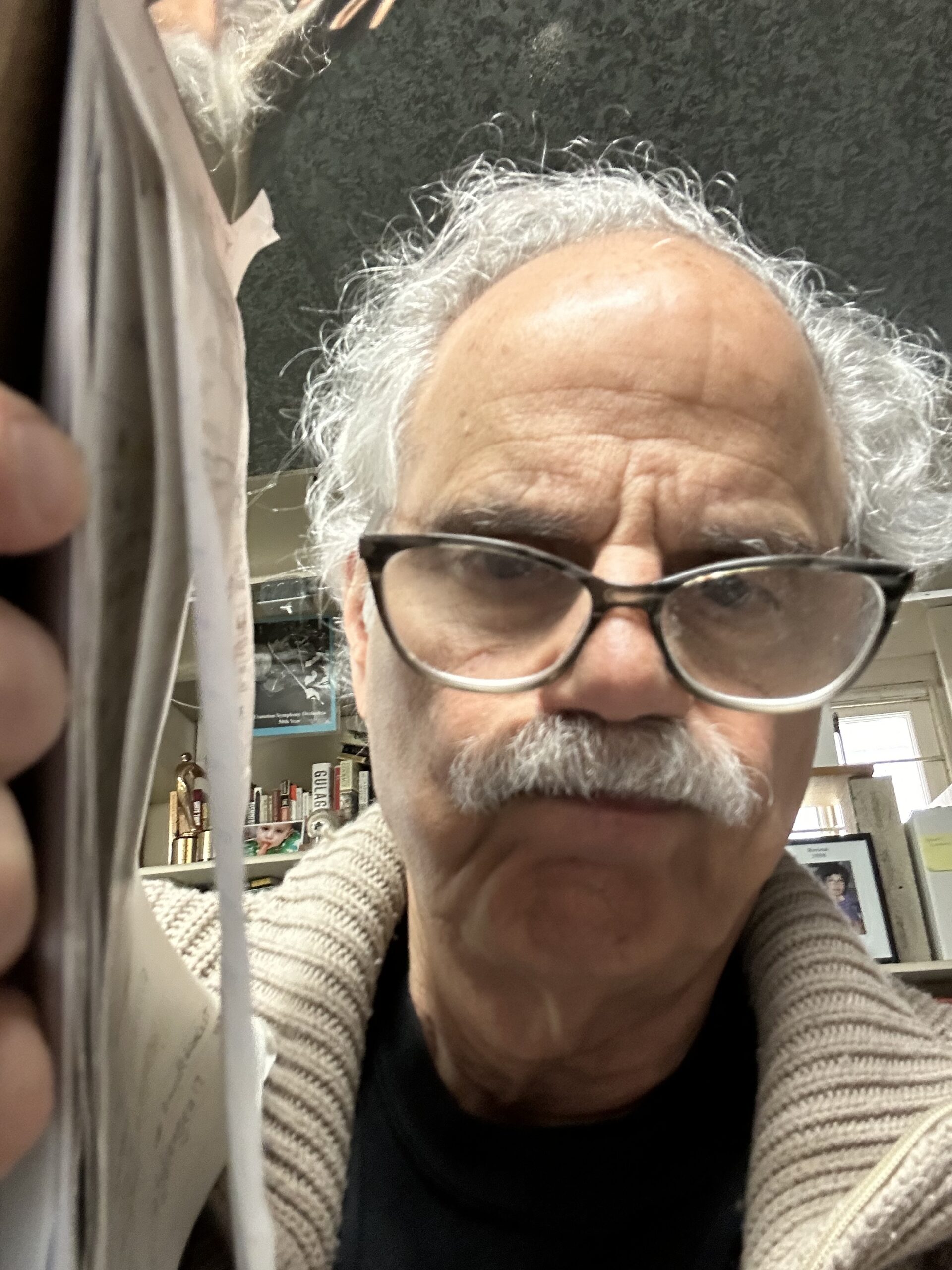

First is laughter. Life would be insupportable without humor. Consider the photo near the top of this column. That’s me with a pigeon perched on my Daily Northwestern cap, taken several weeks ago in the wonderful Parque de las Palomas (pigeons) in Old San Juan. Take it from me: it’s hard to be sad when you find a pigeon on your head.

But there are cheaper, easier and closer ways to remedy the malady of sadness than flying down to Puerto Rico. In the 1960s the author Norman Cousins overcame the ravaging effects of ankylosing spondylitis, a serious, painful and supposedly irreversible degenerative disorder. His self-prescribed medication? A steady diet of Marx Brothers movies and TV comedies. The key to his recovery, he said, was laughter. “I made the joyous discovery that 10 minutes of genuine belly laughter had an anesthetic effect and would give me at least two hours of pain-free sleep.”

He later wrote about his experience in the 1981 best-selling book Anatomy of an Illness as Perceived by the Patient: Reflections on Healing and Regeneration.

Joshing with friends, reading humorous stories and taking advantage of the many hours of comedy that stream online and are available via the Evanston Public Library’s extensive collection of DVDs are ways to lighten the heavy load of existence.

Humor is even a bonding agent, as the late, great Norman Lear described in “the power of laughter to unite Americans.” We could certainly use more of that.

What other L-word remedies are there?

There is lyricism, by which I mean song, music, and all the arts. Darwin surmised that music might have evolved from birdsong, which led in turn to the development of human language, one of the critical hallmarks of our species. Nothing uplifts the spirit as much as the great and enduring works of music – and all the arts. When I’m down, nothing brings me up like this. Or this. Or even this. I could go on almost endlessly with my favorite music, but better you create your own playlist.

And labor and livelihood, the dignity of work. When President Kennedy visited the NASA Space Center in Florida and asked a janitor what he did there, he supposedly told the president, “I’m helping put a man on the moon.” The story may be apocryphal, but the message is true: whether a president or a janitor, your labor helps others and ennobles and elevates us all. As Pope Francis has written, “We do not get dignity from power or money or culture. We get dignity from work.”

Then there’s longevity. As we grow older we become more concerned with and fearful of looming mortality, but hopefully we also gain the wisdom and perspective to understand and deal with it.

And leadership, to be a mentor, teacher and guide, to inspire and educate and thus bring enlightenment and comfort to others.

Literature is another remedy, providing the solace and joy of reading and learning.

And life itself, to cultivate curiosity and develop an interest in all things, because life, even with its sadness and suffering, is endlessly fascinating.

You can put together your own L-word list: lasagna (for great food), lagniappe (gift-giving), leap (taking chances), plus leisure and light and libation, and many more such words which, with a little imagination, might qualify. Even list (as in goal-setting) might make the list.

The last L, which my wife pointed out, is perhaps the most important: love. Love requires connection and connection is how we break free from the sadness of our isolated existence.

As David Brooks wrote in a New York Times column in April 2022, “Suffering is evil, but it can serve as a bridge to others in pain. After loss, many people make a moral leap: I may never understand what happened, but I can be more understanding toward others. When people see themselves behaving more compassionately, orienting their lives toward goodness instead of happiness, they revise their self-image and regain a sense of meaning.”

So yes, acknowledge the sadness, then put it to good use.

+ There are no comments

Add yours