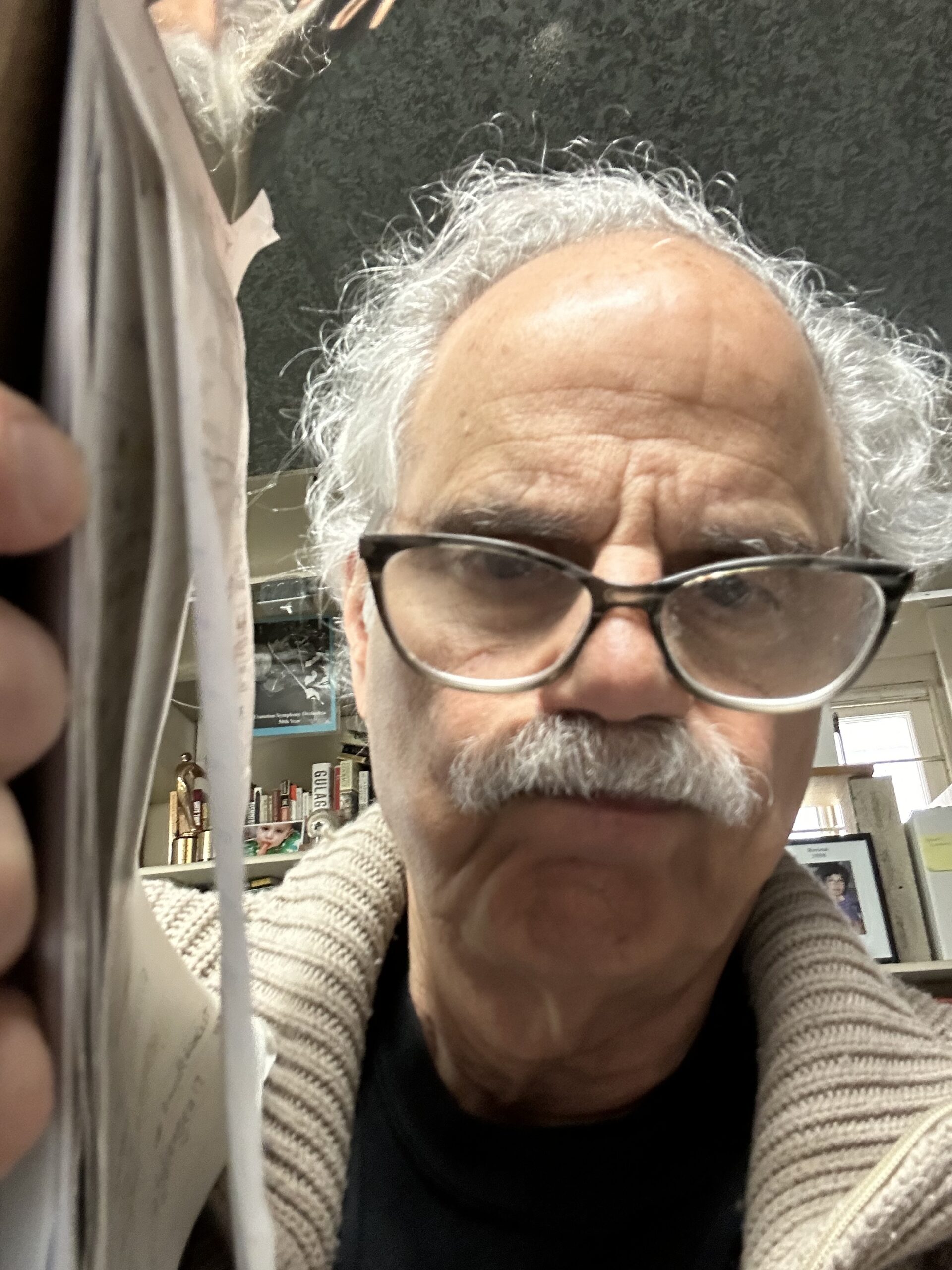

Evanston RoundTable, Oct. 4, 2023

Dad died of lung cancer in October of 1981. I wasn’t there, unfortunately, because I was finishing up my afternoon shift as a business section editor at the Chicago Sun-Times. When my mom called to tell me to get home right away, I couldn’t: I had to put the section to bed.

So I missed the moment he drew his last breath. I missed kissing him goodbye before he died. I missed the chance to tell him I loved him – by 15 minutes.

Our love was complicated. I was a mischievous kid – a sometimes rule-breaker and frequent knucklehead – and he believed in a firm disciplinary hand, specifically spankings, sometimes fairly vicious (it seemed to me), the better to instill the difference between right and wrong. Evidently I needed a lot of instillations.

Worse yet, he did the same with my brother, five years my senior, which was unbearable for me to watch.

Sadly, I never entirely forgave him for all this senseless corporal punishment, which triggered a degree of alienation that sprang up between us. He seemed harsh and authoritarian. I adored my all-loving mother but feared and kept a distance from my dad. Which meant that I never really got to know this most remarkable man.

Evanston with hills

He was born in 1906 in New Rochelle, New York, a suburb of New York City that I like to think of as Evanston with hills. That was still a time when horsepower was provided by horses: There were no cars, no telephones, no rural electricity. As a young man he was reputed to have a hot temper. It was said you could follow his path around a golf course by the trail of his wooden-shafted golf clubs wrapped around the trees.

According to family lore, a few months before he was scheduled to graduate high school in 1923, he told the principal he wasn’t fit to be the school janitor. As a result he was “uninvited” from the graduation ceremony and his yearbook head shot – between Grace Hubel and Marcella James – was excised.

He played semi-pro baseball in the late 1920s – I have a picture of him in a team photo glaring at the camera with all the ferocious seriousness of youth – and supposedly he taught George Gershwin (to whom we were distantly related) to play golf.

His father, William Jacobson, ran a wholesale hardware store at the corner of North and Fifth avenues near downtown New Rochelle. He and his older brother, my Uncle Harold, must’ve worked there as kids. Evidently the business could support only one son, so that spot went to my uncle. With his friendly nature and gift of gab, Dad found a job selling women’s dresses and was assigned a Midwest territory, which is where in 1938 he was introduced to my mother in Chicago. They were married in 1939; in 1940 he adopted her son Mark from a previous marriage. My brother Billy was born that same year and I came into the world in 1945.

A family man and thus deferred from active-duty service during World War II, he worked at the Dodge Chicago plant on the city’s South Side, which built B-29 engines that powered the giant Superfortress bombers that flew over Europe and Japan. According to Wikipedia, it was a historic site: “The Dodge Chicago plant marked an all-time high water mark of cooperation and success between the efforts of the American government, industry, and labor. It also set an early standard for providing an environment of racial and ethnic cooperation and tolerance.”

In 1950 we moved to New Rochelle so he could take a position as sales manager of the New York City office of a nationwide dress manufacturing firm.

In those halcyon years of my youth and his patrimony he became president of the Brotherhood of Temple Israel of New Rochelle, which his father had helped start. He played 18 and sometimes 36 holes of golf every weekend, and I have a small article from the Chicago Daily-Tribune of Sept. 30, 1944, under the headline “Hole in One” that reads: “Lester E. Jacobson, Cog-Hill, fourth hole, 142 yards.”

Bonding over baseball

On Saturdays he would sometimes take me with him to his office in New York’s Garment District. It was there I learned to hunt and peck on a typewriter, a technique that bedevils me to this day. While he worked, I would sometimes wander around midtown Manhattan, then a pretty seedy environment of peep shows and adult bookstores, agog at the tawdry splendor.

But the primary bond between us was baseball. He took me to the Polo Grounds to see Willie Mays play for his beloved Giants. He and my oldest brother Mark were at the first game of the 1954 World Series when Willie made “The Catch.” Dad took me to my first World Series game in Yankee Stadium in 1956. The Yanks beat the Dodgers 6-2, and my idol, Mickey Mantle, helped win the game with a home run. I was ecstatic. He also had two tickets to the game the next day, but announced we couldn’t go – it was a Monday: a workday and a school day. So he gave the tickets away and we missed seeing Don Larsen pitch the only perfect game in World Series history. He got to watch it anyway, in a fashion: He and some of his colleagues went to the Oyster Bar restaurant at Grand Central Station for lunch. As they were leaving, they stopped at the TV over the bar and decided to wait for the first hit. Of course, it never came.

In May 1961, we went to a Sunday doubleheader between the Yankees and the Baltimore Orioles. We were sitting in the upper deck, behind home plate, with two outs in the top of the ninth when I was dispatched to get some refreshments between games. I hovered at the portal awaiting the last out when the Orioles’ Brooks Robinson, facing Whitey Ford, lined a hard foul straight at me. Reflexively I reached up with one hand and grabbed it. “Dad, did you see that? Did you see that?” I shouted with glee after the fabulous catch. He nodded yes, but in that curious clairvoyance sometimes granted to youth, I knew he hadn’t. Nevertheless, it was a thrilling moment for both of us.

After he lost his job in New York, we moved back to Chicago in 1963, immediately after I graduated from high school, so he could take another sales position at a dress manufacturing plant on the Northwest Side.

Our biggest falling out came a few years later. We were on opposing sides of the dreaded “generation gap.” I suggested at dinner one summer night that the Vietnam War was a big mistake. An ardent FDR Democrat (I have a letter dated July 7, 1932, signed by Roosevelt, thanking my father for his support at the recent Democratic convention), he had no patience for such temerity and as much as challenged my maturity and intelligence to make such an outlandish statement. We had harsh words and I walked out.

What happened next was striking. I vividly remember it was a lovely June evening. I made my way around the block to a bench outside the Lincoln Park Conservatory near Fullerton Avenue. Amid happy scenes of children laughing and frolicking, I broke down in sobs. I might have disputed his politics and hated his peremptory manner, but I couldn’t do without his love – even if I didn’t have his approval.

Nevertheless, though he never said as much, I think he was tickled when I spent a year abroad – what would now be called a gap year – hitchhiking through Europe and making my way to Israel. I think he must’ve been delighted when I married into a large and loving Jewish family from Rogers Park, and was happy to see me advance in my career as a Chicago journalist. One time he and Mom came by the Sun-Times newsroom. I showed them how I had edited Mike Royko’s column in the paper that day.

A surprising apple

Later, after he died, I asked my brother Mark what Dad actually thought of me. “Oh, you were the apple of his eye,” he said. I was bowled over. What? Why hadn’t he ever evinced such a tender regard?

Why indeed. Why had I never asked him about his upbringing? About playing semi-pro baseball or what it was like to know the great Gershwin? About helping to build those giant B-29 bombers? About driving around the country selling dresses from the trunk of his car? Or growing up before cars, highways, electricity? Working in Manhattan when New York and America were at the peak of their supremacy? Why didn’t I ever sit down and interview him about his remarkable past, which spanned a century that went from horseback to men hitting golf balls on the moon?

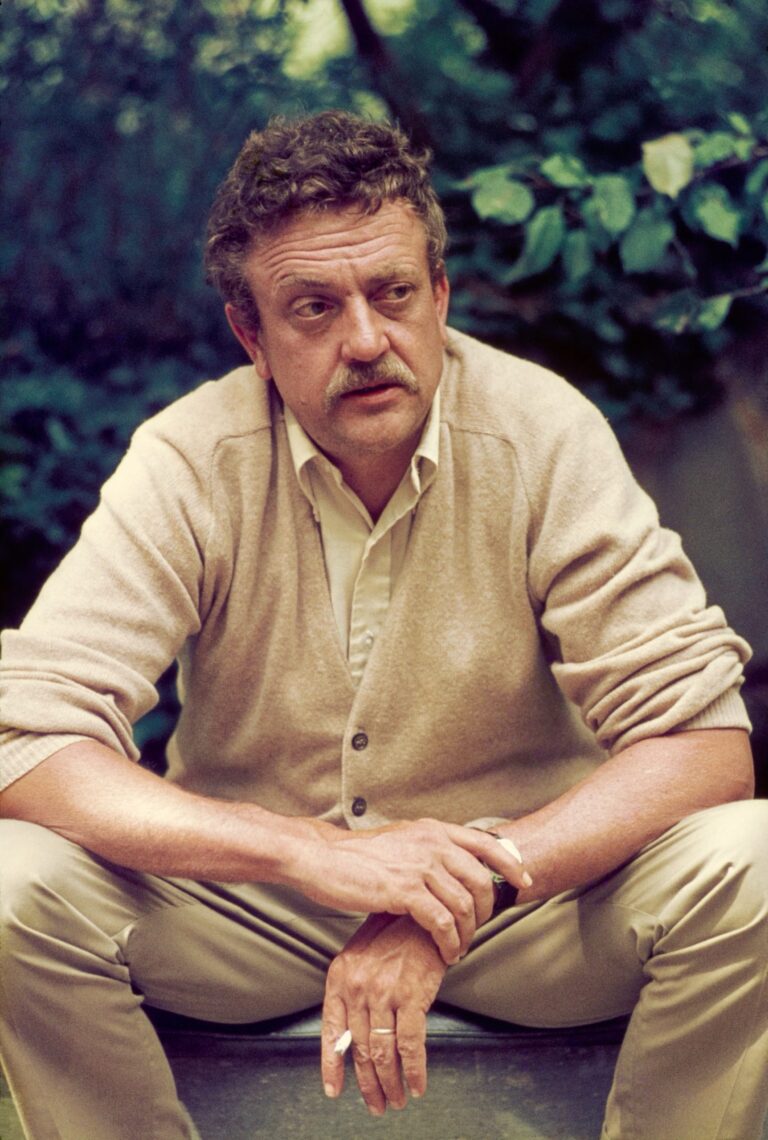

He was exceptionally bright, self-educated, a regular reader of books and newspapers. Also philosophical, amused by the world, a student of people. He made his way through The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, he said, in order to compare it to the inexorable decline and fall of the American empire. He loved Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley and talked about the two of us traveling together to San Francisco, his favorite city. Would that we had.

Once, as I visited my parents on a Saturday morning before heading to the Sun-Times to work on the Sunday paper, he invited me to walk with him through Lincoln Park. Still conflicted after all these years about our relationship, I demurred. But then as I was driving away I had second thoughts and tried desperately to spot him, to park and join him. No luck.

Just days before he died, in great pain and unable to speak because the lung cancer had eaten away at his esophagus and throat, he listened impassively as I told him I was never prouder of him than at that moment, for his great courage and resilience.

He didn’t respond, and I’ll never know if it meant anything to him. Perhaps. At least it was something.

‘Two great men have died’

He passed away Oct. 5, 1981. When Egypt’s Anwar Sadat was assassinated the next day, my mother announced, “Two great men have died.”

My oldest brother Mark, whose judgement I greatly respected, was crazy about him. “Didn’t it upset you, all those spankings?” I asked him. “Nothing you didn’t deserve,” he said with a shrug.

Dad loved a good joke (especially puns, the more groan-worthy the better) and liked wordplay (especially palindromes), had exquisite penmanship and looked forward to (and usually completed) the New York Times crossword puzzle every day. He enjoyed being told he looked (and sounded like) Bogart and loved Big Band music. He saw Benny Goodman and his band perform at Chicago’s Congress Hotel in 1939 before they went to New York to record their famous Carnegie Hall concert.

He wrote my mother, a few days after they were married, the most extraordinarily passionate love letter. Yet my wife and sisters-in-law thought “Big Les” imperious and patronizing. He had forearms like Popeye and was still strong and athletic even into old age.

My best friend Jay and I took him, dying of cancer, to a Cubs game. When the Cubs rallied from behind late in the game, and there was a tremendous roar from the crowd that brought us to our feet, I looked down to see him with a broad smile. He still loved the game, the roar, the crowd, the excitement – life.

Hardly a day passes that I don’t think about him. Sometimes he comes to me in a dream: “Stop your belly-aching!” he commanded one night during a bad patch. I’ll recall corny jokes he would make or observations about people and places, the family holidays we took to Sebring, Florida, or our college campus visits to New England.

I’ve written before about the benefits – cognitive and familial – of writing a memoir, in part to tell people about the enormity of your life. Every life encompasses multitudes and has great historical and personal value. It’s never too soon or too late to share your story with your family and friends, in the process learning more about yourself and helping others to learn more about themselves.

I wish I had encouraged my old man to do just that. It would’ve been quite the story.

Les-thanks for sharing another family story from the past! Soni