Evanston RoundTable, Nov. 8, 2023

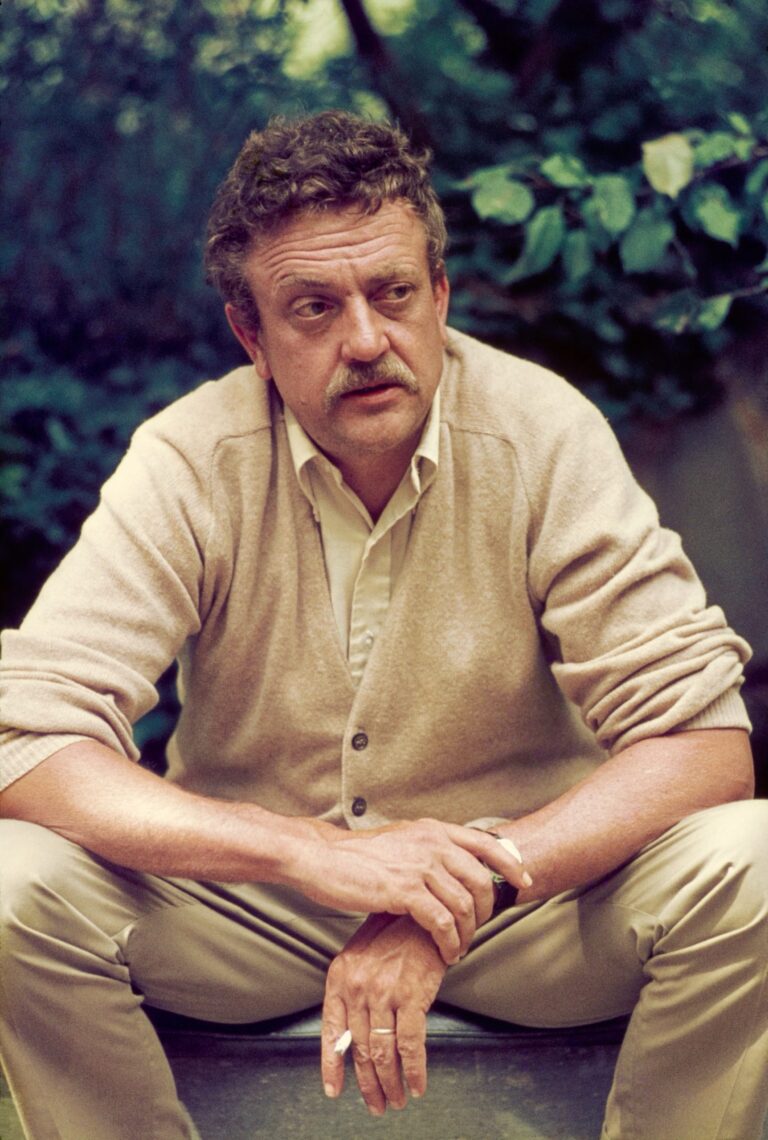

Fifty years ago, in June 1973, the great Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich came to Evanston to receive an honorary degree from Northwestern University.

He spent three days here, his first visit to the American Midwest, squired by Irwin Weil, then Professor of Slavic Languages and Literature at the university, who served as his guide and translator.

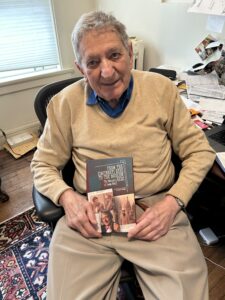

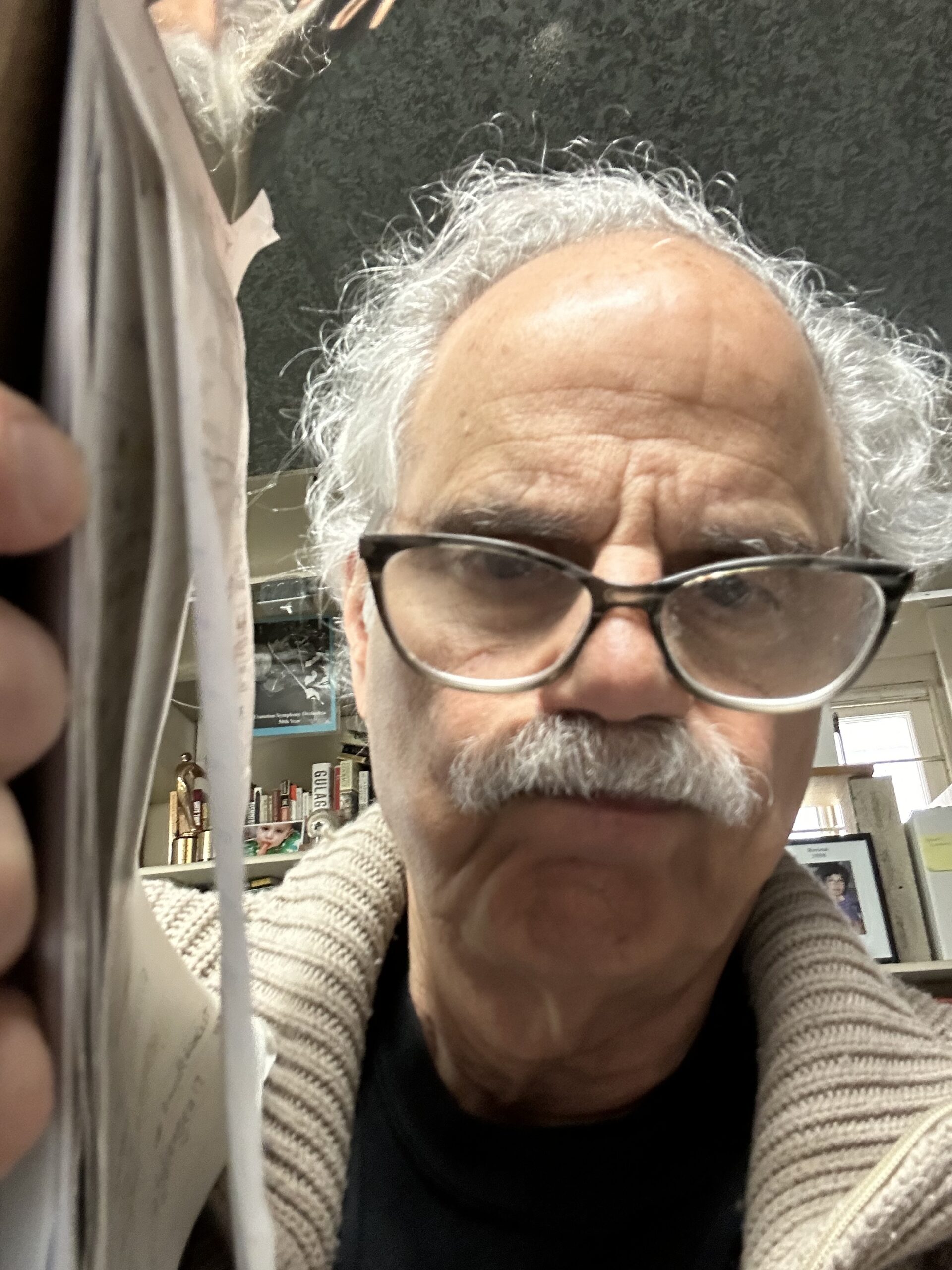

Weil, now 95, fondly remembers the time he spent with Shostakovich. “He was a wonderful person to be with,” Weil recalled from his home in northeast Evanston, a mile from campus, where has lived for more than half a century. “He would good-naturedly correct my Russian grammar. When the music students played one of his compositions, he was delighted and smiled and waved at them.”

The retired professor recalled that when Shostakovich found out his driver was getting married the next day, “he insisted they stop so he could properly congratulate him.”

‘Swirl of publicity’

Weil spells out Shostakovich’s visit – and the June 16 commencement exercises – in some detail in his memoir From the Cincinnati Reds to the Moscow Reds.

“You can perhaps imagine how emotionally charged the events were around the June commencement,” Weil wrote in the 2015 book. “Shostakovich came to the Chicago area in a whirl and swirl of publicity. Large numbers of people wanted to meet with him, and there were numerous receptions and interviews. … The interest was overwhelmingly friendly, perhaps best typified by a touchingly earnest young man who cried out from a large group Ia liublu Vashu nebesnuiu muzyku (I love your heavenly music), with the ‘u’ sounds so blatantly turned into American diphthongs that [Shostakovich] and his wife exploded into good-natured laughter.”

Weil wrote that ordinarily, honorary degrees during June commencement exercises at Welsh-Ryan Arena drew only perfunctory interest from the audience. “However, in Shostakovich’s case, thousands of people stood up, with cheers roaring like a storm, and with sustained applause led by the music students. Dmitri Dmitriyevich [the composer’s patronymic] was deeply touched…”

Not all went entirely well, however. At a pre-commencement news conference at Northwestern’s downtown campus June 15, Weil said one music critic “peppered [Shostakovich] with hostile questions. Who was behind his trip? What kinds of political machinations were involved. What purpose could there possibly be in Soviet music?

“[He] even had the gall to ask Shostakovich, in a nastily hostile tone, ‘What the hell do you know about twentieth-century music?’ Shostakovich handled such moments with great dignity and very simple answers. He said he had gladly accepted a friendly invitation, and he could only judge twentieth-century music from what he had heard, but was pleased to have the chance to learn more about contemporary music.”

Meeting of composers

Weil helped facilitate such a learning moment, hosting a meeting between Shostakovich and several American composers at which they listened to and discussed their work. “In each case, Shostakovich got right to the heart of their music,” Weil recalled.

During their time together, Weil wrote, Shostakovich “expressed a lively interest in American life and politics. He asked many questions about the presidential election campaign, which had taken place about eight months earlier, and he was intrigued to find out the basis of many American intellectuals’ antipathy toward Richard Nixon. It was easy to hear in his questions the-then typical Soviet-educated approach to American conservatives: Russian thinking people – smarting under a repressive regime – saw in American conservatives a counter force against Communists. Nixon could often be counted on to say exactly what the Soviet intellectuals would have liked to have said, if they dared. There were exceptional people, like Solzhenitsyn and Sakharov, who spoke their opinions openly, but they were rare. Shostakovich was willing, in very private conversation, at least to hint at his angry views about the Soviet regime, but he almost always stopped before expressing these opinions openly. He was in many ways a very frightened man, both for himself and for his family. It was not hard to understand the basis of his fright.”

A Chicago Daily News article from that week added more details about Shostakovich’s visit. The composer “praised Chicago as ‘the city of art and science,’ expressing admiration for its architecture and people.” The article noted that the composer “talked about music and Soviet life, but in a generally evasive and noncommittal way, seemingly showing the effects of over half a century of indoctrination and harassment by Communist policymakers.”

Shostakovich died two years later in Moscow at the age of 68. “Shostakovich’s reputation has continued to grow after his death,” according to Wikipedia. British composer William Walton called him “the greatest composer of the 20th century” and musicologist David Fanning wrote that, “Amid the conflicting pressures of official requirements, the mass suffering of his fellow countrymen, and his personal ideals of humanitarian and public service, he succeeded in forging a musical language of colossal emotional power

Thank you Lester for helping me learn

about stuff that I would never have delved

into without you and your writings.