Evanston RoundTable, Aug. 3, 2022

In one movement of less than 10 minutes the master offers a lifetime of sonorous beauty and worthwhile lessons.

Bach and Beethoven are the two giants of classical music, the twin peaks of composition, the K2 and Everest of sonic sensuality. Whether you prefer one or the other depends on your musical sensibility, stylistic preferences and even your mood at the moment.

Bach is generally considered more intellectual, more abstract, more complex. “Bach is written for the cathedral,” Yehudi Menuhin said. Baroque polyphony is like that: many voices echoing brilliantly throughout the church. But Bach wrote beautiful simple melodies and Beethoven wrote exuberant fugues.

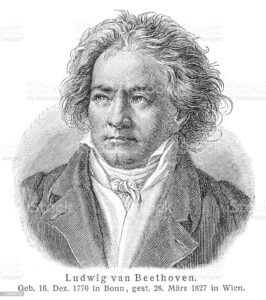

Beethoven might seem paramount. “Widely regarded as the greatest composer who ever lived, Ludwig van Beethoven dominates a period of musical history as no one else before or since,” wrote Britannica.com.

Not so fast. “Johann Sebastian Bach has been voted the greatest composer of all time by 174 living composers for BBC Music Magazine’s December 2019 issue.”\

I prefer Brahms myself, the great synthesist of Classical and Romantic styles.

But there is plenty to love – a lifetime of great music to absorb, appreciate and even learn from – in the work of all three.

Take the opening movement in this sumptuous live performance of Beethoven’s Opus 74, the so-called Harp Quartet, a nickname derived from the many plucked (pizzicato) notes, like a harp. The piece is in the key of E-flat major, a favorite of Beethoven’s and known as “a heroic key, extremely majestic, grave and serious.”

Sure enough, the piece starts with a slow and sometimes mysterious introduction, punctuated by sudden and sharp sforzando chords and dissonant intervals. Life is like that: unfathomable and sometimes harsh, but capable of great beauty and consolation.

At 1:58 the allegro (fast) movement starts in earnest with a great chordal flourish. Immediately Beethoven introduces the primary theme, a simple five-measure melody in the first violin repeated by the viola. As is often the case with Beethoven, it is what he makes of the simple theme that is increasingly magnificent. A new theme emerges right after, punctuated by the eponymous plucking notes, and set off with additional sharp szforzando chords like little sonic bombs. Again, the thought suggests itself: rarely does life permit us uninterrupted serenity; harsh reality almost always intrudes.

After this episode, fast 16th-note passages lead at 3:08 and again at 4:38 to a kind of preview of the movement’s close, followed by more bombastic chords that re-introduce the movement’s allegro opening. Note at 3:40 how the four instruments – two violins, viola and cello – take turns with the pizzicato passage “tossed from one instrument to another against a background of repeated chords,” wrote Philip Radcliffe in his book, Beethoven’s String Quartets.

Note also starting at 3:52 how the second violinist looks over at the first. Eye contact is critical in chamber music, where there is no conductor to cue the players. Frequent eye contact enables players to know when to synchronize their entrances, how to play off each other, even what part of the bow to use to sound consistent. Chamber musicians often look at each other more than down at their parts, which they know from repeated practicing, rehearsals and performances almost by heart.

(Some string ensembles memorize all their music, the better to play straight from the heart – and not through the eyes – though I believe there is some element of bravado involved too.)

At 4:49 the music slows as if preparing us for some major new development, but it’s a feint, a tease: the players return to the opening theme once again, only this time moving into new territory: a dip into minor key, before reverting at 5:06 to another version of the simple opening songlike melody played beautifully by the cello.

This introduces a section of wild 16th-note fast passage work by the two inner players – the second violin and viola – while the first violin and cello trade off the singing melody. A note (pun intended) about the inner voices of a quartet. “Second fiddle” is a sometimes-disparaging term for someone who doesn’t measure up, who can’t make it as first fiddle. Nonsense. As all good string players know, there’s a world of richness playing the inner harmonic parts. Everyone in a good quartet, as in any good team, has a critical role to play in support of the whole. (When President Kennedy, while touring NASA headquarters in 1962, asked a janitor what his role was, the man famously replied, “I’m helping put a man on the moon.” Even if the story is apocryphal, its lesson is truthful.)

After the wild abandon of this section the music starts to slow, at 5:45, coming almost to a stop, as if exhausted. Again the pizzicato notes are tossed around from player to player, at first slowly, in quarter notes; then faster, in triplets; and then faster yet in 16th notes. This is classic Beethoven: taking a few innocuous-seeming elements and expanding on and varying them to create exciting and satisfying contrast.

At 6:25 we’re back to the opening allegro statement. Aside from the pizzicatos observe the profusion of small, short bouncing bows (for instance from the first violinist at 6:59 and the second violinist at 7:20), so called spiccato (“robust, marked” in Italian) bowing, a challenging technique to bounce the bow and yet keep it under control. Looks simple, but as in life, skills that appear easy often take repeated and relentless practice and finesse, as in Malcolm Gladwell’s supposed 10,000 hours rule of repetition and rehearsal to achieve mastery.

The quartet sails along reworking these themes and techniques until, at 8:00, the start of something remarkable happens. Again the music slows, suggesting some portentous drama, and sure enough at 8:38 it happens! The first violinist erupts with a volcanic onslaught of 16th notes (so hard to play cleanly and in time) while the cellist plucks the pizzicato theme and the inner voices finally get a chance to shine, making the most of their brief foray with the songlike opening theme, taking it to new heights of beauty and serenity before everyone lands together on the opening tonic of E-flat major at 9:17. Beethoven reprises the pizzicato theme one last time, bringing the remarkable movement to a close.

“In all this passage,” Radcliffe writes of the extraordinary ending, “Beethoven achieves a truly symphonic breadth and spaciousness without any sense of strain on the medium.”

In one movement of less than 10 minutes the master offers a lifetime of sonorous beauty and worthwhile lessons. In his deafness, illness and loneliness, Beethoven endured years of hardship and tragedy. But still another lesson, perhaps the most important: one can overcome seemingly insurmountable odds with effort and determination to give the world something beautiful and profound – such as a janitor putting a man on the moon or a deaf man writing a beautiful string quartet.

Very knowledgeable and very well written.