Evanston RoundTable, May 26, 2021

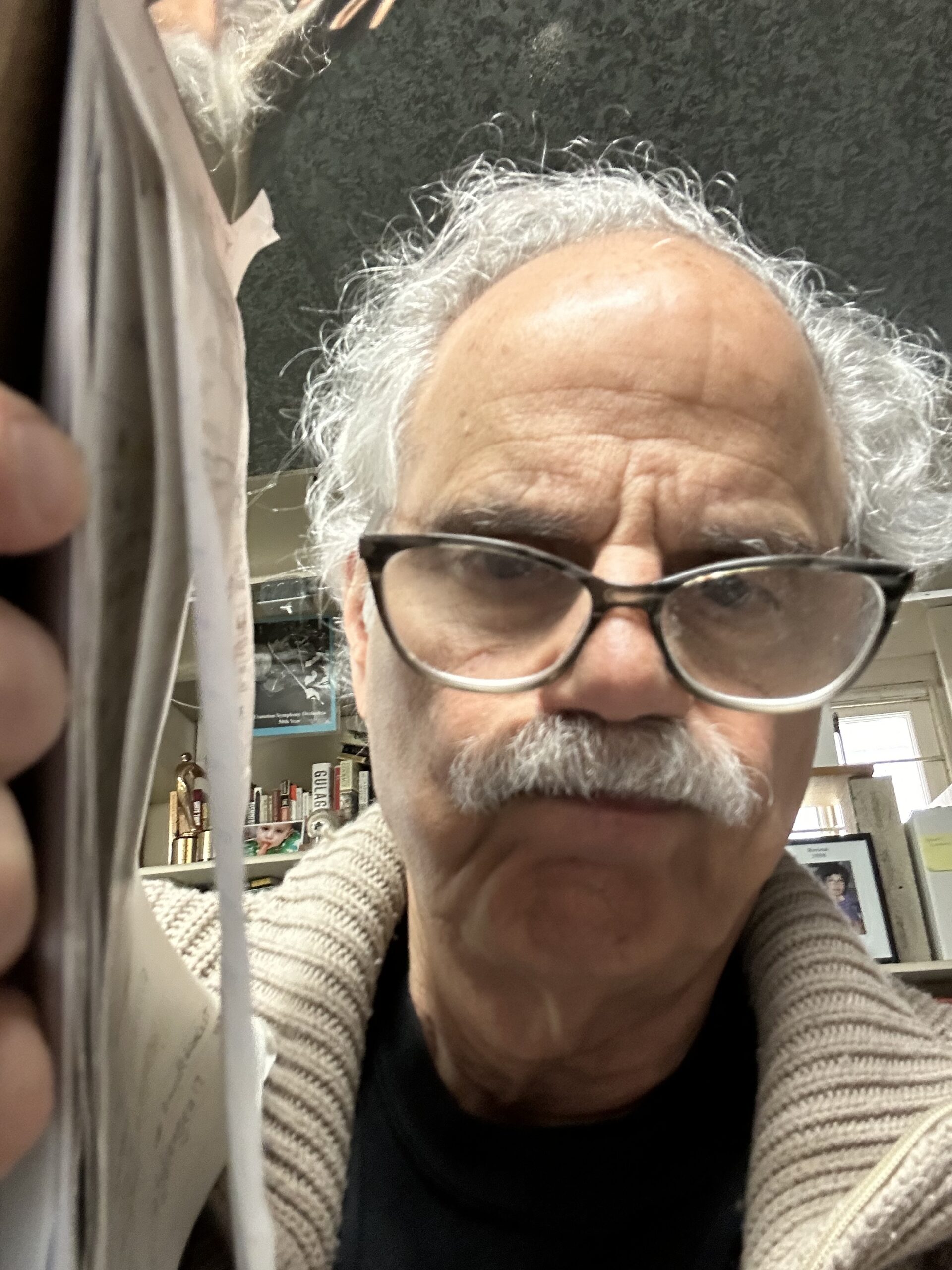

Longtime Evanston resident and renowned journalist and author Henry Kisor knows a thing or two about challenges. At 3½ he lost his hearing after an almost-fatal bout of meningitis. “For many parents,” Mr. Kisor wrote in “What’s That Pig Outdoors: A Memoir of Deafness,” published in 1990, “the verdict of deafness is like a death sentence for their child. How, they ask distraughtly, will their youngster be able to grow up to be a functioning member of society instead of being ‘deaf and dumb,’ a representative of a less-than-human species to be pitied and scorned if not simply ignored?”

To their credit, his parents embraced the education of their young deaf child with determination and sagacity. They were, in his words, “intelligent, cultured, and tough-minded.” Henry’s mother refused to offload her child to an institution and took on the daunting (and then unusual) task of home schooling him. To his parents in 1944, residential schools for the deaf were “nothing more than holding tanks for the hopeless.”

Mrs. Kisor discovered and became adept at the “Mirrielees” method, named after the teacher who taught parents to demonstrate to their deaf children how to learn to speak and read lips – known as “oralism” in the deaf world. “A highly unconventional teacher for the deaf, Doris Irene Mirrielees [was] a committed ‘oralist’ who spurned any reliance on sign language,” wrote author Jim Miller. “Mirrielees insisted on teaching deaf children to read books, to read lips, to write, and, eventually, to speak.”

Meanwhile Henry’s father accepted a marketing job at Montgomery Ward in Chicago, so the family relocated from New Jersey to Evanston. His parents insisted that their son be academically mainstreamed, and to its credit the school district agreed. Off he went to Orrington, Haven, and then Evanston Township High School.

In his memoir Mr. Kisor describes his “average American upbringing,” deafness notwithstanding, frequenting the McGaw YMCA and attending the Y’s Camp Echo, first as a camper and then a counselor. He also played softball and swam competitively.

Swimming was particularly important, he said, because it allowed him to “compete with hearing athletes as an equal.” But as he topped out in ability in his mid-teens, something else came along to replace it that profoundly influenced his future. As he wrote in his memoir: “My sophomore English teacher [at ETHS], who apparently had never heard that the verbal skills of deaf students are supposed to be deficient, suggested to the journalism teacher that I might make a good candidate for her course as a junior. Though I had no idea what journalism entailed – the notion brought to mind a vague mental picture of a grizzled newspaperman in a fedora, dribbling cigarette ashes on his typewriter while barking commands into a telephone – I accepted her invitation to take the course. It was the best decision I had made in my young life.”

Turns out young Henry was a good writer and, an especially valuable skill in mid-1950s journalism, a handy copy editor with the ability to rewrite messy stories.

“As a rewrite editor,” he wrote, “I found I had a definite knack for the shape of a story, for reducing it to its ‘who-what-where-when-why-how’ components and reassembling these facts in the most efficient and pleasing manner. Once the stories were done, the next task was to assemble them, together with photographs, on the page, and then write a headline for each. For these things I also had a flair, and I also got along well with my fellow editors-in-training. At the end of the year I was appointed managing editor, or second-in-command, of the school paper.”

Thus a highly distinguished career was born.

He followed his older brother to Trinity College in Hartford, Conn., and after graduating in 1962 returned to his hometown to attend Northwestern’s Medill School of Journalism, where he studied under, among others, Richard Stout, later the Washington correspondent for Newsweek.

After a short stint on the copy desk at the Evening Journal in Wilmington, Del., where he also wrote book reviews and a literary column, he began an illustrious run at the Chicago Daily News in May 1965.

The following year was also momentous. That was when he met Debby, his future wife. “She says that the idea of going out with a deaf man on a blind date almost overwhelmed her, and her roommate had to push her down the stairs to meet me.”

Also important at the time was the introduction of new if still crude technologies to help the deaf communicate with the hearing world, such as the “Sensicall” device to facilitate phone communication.

“Those who hear cannot imagine how grindingly lonely deafness often can be,” he wrote. “A comfortable home can feel like a maximum-security prison if there is no easy means of communication with the outside. This is one important reason why the deaf tend to gravitate toward one another.

“I learned to handle social isolation early on as a deaf person, to use solitariness to my advantage – as a writer, especially. Speech-to-text apps helped in many ways when I needed to communicate with someone.”

The new technologies plus state and federal equal access and entitlements laws meant that each succeeding decade brought improvements that helped connect the deaf and hearing worlds.

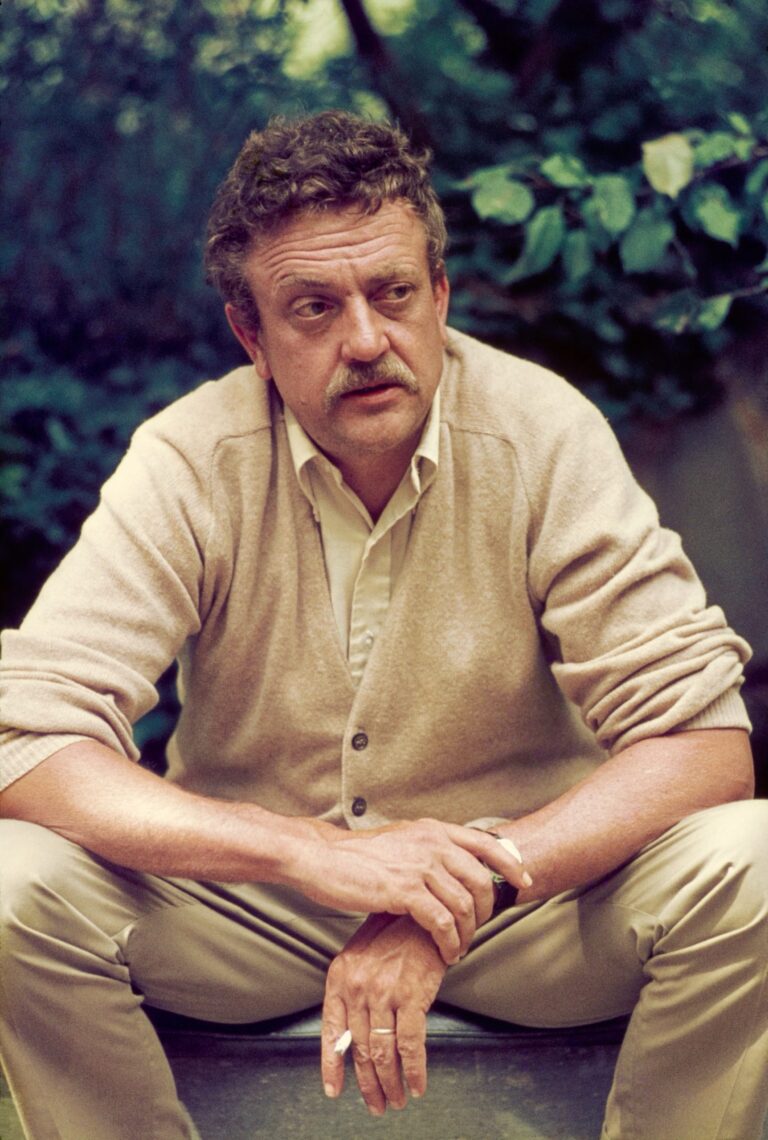

In 1975 Mr. Kisor became the book editor at the Chicago Daily News and when the paper folded in 1978 moved to its sister publication, the Chicago Sun-Times. As part of his job he visited and interviewed many illustrious authors, including Margaret Atwood, Tom Wolfe, Nelson Algren, Bernard Malamud, Joseph Heller, William Styron, Tracy Kidder, Elmore Leonard, Susan Cheever, and Ved Mehta.

To compensate for the difficulty of conversing with his subjects, Mr. Kisor prepared extensively for his interviews, and the research paid off. “When William Styron ushered me into his Connecticut home, he seemed chilly and suspicious, as if a deaf writer interviewing an author was a People magazine notion like photographing him in his bathtub,” he wrote in a Daily News alumni newsletter. “By then I had hit upon the gambit of devoting the first question to some obscure point in the book, to demonstrate that I’d done my homework. When I did that for ‘Sophie’s Choice,’ Styron slapped his leg in delight. He gave me two hours instead of the customary 60 minutes, and it was one of the best interviews I have ever had.”

Something Mr. Mehta, who was blind, said during their interview helped him re-think his deafness.

“A few weeks before, I had overheard two people talking about me,” Mr. Kisor wrote in his memoir. “One called me ‘the Sun-Times’ deaf book editor.’ That irked me, for deafness is not part of the way I define myself. Doesn’t it also irritate Mehta when people call him ‘the blind New Yorker writer’ [Mr. Kisor asked him during their interview]? ‘As I grow older it matters very little what people think or say,’ he replied. ‘You can’t change what people think of you. People are what they are. But a time comes when you’re defined by what you’ve done. People don’t consider that the ‘deaf Beethoven’ wrote the Ninth Symphony or that the ‘blind Milton’ wrote the later poems. It’s a matter of what you achieve at the end of the road.’”

Mr. Kisor wrote that he was: “…book editor and literary critic, husband and father, son and brother. ‘Deaf man’ brought up the caboose of that train of self-characterization.”

There followed a train of awards and distinctions. In 1981 he was a Pulitzer Prize finalist for criticism. He taught writing at his alma mater Medill. Later he launched a syndicated column on personal computers. He has written six novels and four non-fiction books. In 2001 he was inducted into the Chicago Journalism Hall of Fame.

“What’s That Pig Outdoors” (the title comes from mishearing something his son said to him) was “extravagantly praised,” he wrote, and the book’s royalties helped put his younger son through college.

He followed that in 1994 with “Zephyr: Tracking a Dream Across America” about the famed California Zephyr train that runs from Chicago to San Francisco. The New York Times reviewer said, “He follows his dream across half the continent on his favorite train, generously taking other dreamers and imaginers along with him. It’s a wonderful ride.”

In 1997 he published his account of acquiring and learning to fly a Cessna-150, “Flight of the Gin Fizz: Midlife at 4,500 Feet.” Despite being unable to hear airfield radio communications and thus confined to airports and landing strips without control towers, he managed to fly more than 4,000 miles and realize his dream of retracing the deaf aviator Calbraith Perry Rodgers’ trailblazing 1911 flights across America.

“I wanted to do something other people couldn’t do,” he said. “When you’re at 5,000 feet all by yourself, nothing can touch you. If something interests you, you fly over there and take a better look at it. Like the eyes of God.”

“What Kisor allows us to share is… one man’s almost giddy sense of stepping into another dimension of living, his awareness that he is becoming a hero to himself. He will never be the same, lucky fellow,” wrote the New York Times.

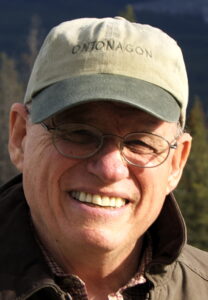

Since then he has written a string of mystery novels featuring a Lakota-born, white-raised sheriff named Steve Two Crow Martinez. The books are set in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan where the Kisors have a summer home. “As an Indian reared in a white world and as a deaf person brought up in a hearing world, [Martinez] and I both often felt as if we had fallen between two stools,” Mr. Kisor wrote. “In fact, deafness is involved in one way or another in all my books.”

In all this Mr. Kisor enjoyed a great deal of professional aid from Debby, who was a teacher and librarian at St. Athanasius and Haven Schools in Evanston and Red Oak School in Highland Park, as well as children’s book columnist at the Daily News and Sun-Times. She also went along with him as a communications assistant on his book travels.

In 2006 he retired from the Sun-Times, capping a 42-year career in journalism. But he continued to write. His most recent book, “Traveling with Service Animals: By Air, Road. Rail and Ship Across North America,” published by University of Illinois Press in 2019, was inspired in part by Trooper, his little black service schnoodle. “My co-author and I are hoping to do a second edition of that for when post-COVID travel opens up again. Like everyone else…Trooper and I both are anxious to hit the road again.”

For many years the Kisor family (including their two boys Colin and Conan) lived at a home at Harrison and Ewing. In 2013 they moved to a condo building at Central Street and Central Park Avenue. In 2019 they downsized again and moved to Three Crowns Park. “Congregate living is like condo living but with communal dining rooms,” he said, “and in a retirement community of this size (about 150 residents), you know your neighbors. Plenty of privacy if you want it, plenty of company when you want that and, lots of interesting lectures and events, at least in pre-COVID days. And, COVID aside, you have complete freedom to travel.

“When we moved into Three Crowns, I saw possibilities in a mystery novel set in a retirement community, and got about 100 pages into one before COVID came along. No mystery set in the present day is going to be able to avoid dealing with COVID, and we don’t yet know how that is going to play out. So the novel has been shelved for the time being.

“I keep busy with my portable model railroad and nature photography,” he said. “Soon we’ll go up to our cabin on Lake Superior and I can chase more birds with a telephoto and Trooper can try to nail more chipmunks.

“Because of Trooper, I’ve become a bit of a vocal disability rights advocate. Getting refused by an Uber or Lyft driver, or being told to leave a restaurant, because of my service dog gets my hackles up, probably more so because I’m old and crotchety. I must say, however, that almost never do I have trouble in Evanston, because it’s a highly enlightened university town and everybody seems to know about service animals. Many restaurants go out of their way to make us comfortable.”

In “What’s That Pig Outdoors,” Mr. Kisor devotes considerable space to parsing the pros and cons of lip reading vs. sign language, each of which had its passionate advocates. “But these days,” he says, “deaf people generally agree that every case of deafness is different and that we are not a monolithic community. Of course there still are communications ideologues but they’re growing fewer.

“An increasing number of deaf people have cochlear implants and use American Sign Language as well as speech and lipreading. Those lucky souls, usually younger adults, can ‘code-switch’ between the speaking and signing communities … and double their chances of getting a date on Saturday nights.”

As for trying to read lips at a time when most people are masked, technology has made all the difference. Mr. Kisor uses Otter.ai, an audio recording app that converts speech to text. “Otter picks up the speech provided the speaker speaks at a sufficient volume,” he explained. “Masks do muffle speech some, but I haven’t noticed by a lot.”

“Life without hearing has been fine and fulfilling,” he wrote in his memoir. Wrapping up this profile I asked him to expand on that statement. I expected his response to be lengthy. After all, he will turn 81 this summer and his career has been long and triumphant, especially in view of the challenges he had to surmount.

But I forgot he started his journalism career as a copy editor with rewrite skills, trained to “write tight.” This is what he emailed back: “For the Irish playwright Brendan Behan, in the Depression ‘getting enough to eat was an accomplishment. To get drunk was a victory.’ For this deaf person, working for a good living is an accomplishment. Living an ordinary life is a victory.”

+ There are no comments

Add yours