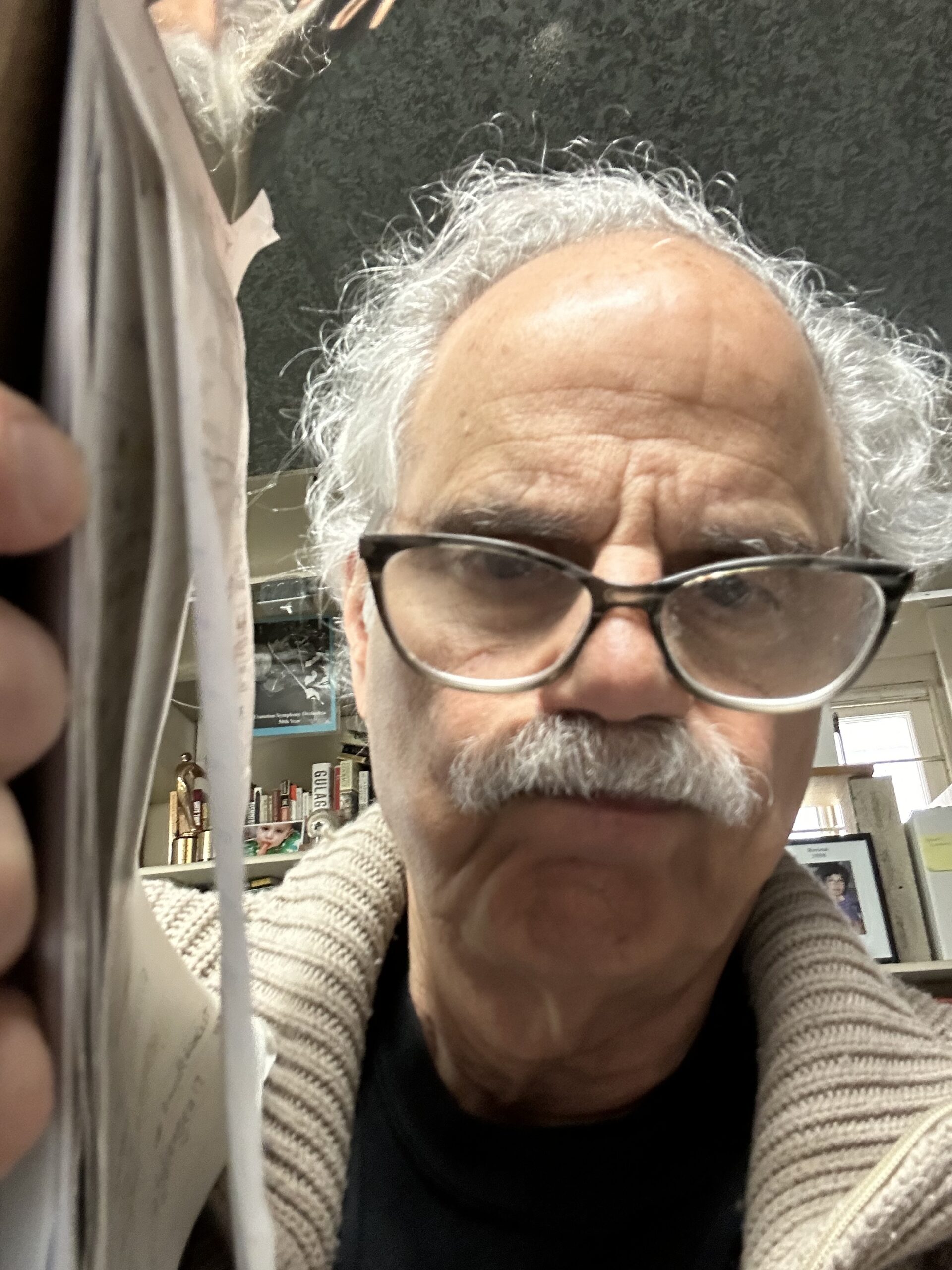

Evanston RoundTable, June 7, 2023

Gary Saul Morson’s latest book examines life’s great questions as explored in the classic Russian literature of the 19th and 20th centuries, in novels and short stories by such masters as Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Chekhov, Solzhenitsyn and Pasternak.

Morson, the Lawrence B. Dumas Professor of the Arts and Humanities at Northwestern University, is the author or co-author of 13 books (including two with former NU President Morton Schapiro) and the editor or co-editor of another eight. He’s also written some 200 full-length articles, another 50 op-eds and short interviews and 35 book reviews. His extensive CV lists scores of honors and prizes, including the Career Outstanding Scholar Award of American Association of Teachers of Slavic and East European Languages; the LeRoy Hall Award for Teaching Excellence, Northwestern University; and the Sidney Award for Best Long-Form Essays of 2017.

Wonder Confronts Certainty: Russian Writers on the Timeless Questions and Why Their Answers Matter, published in mid-May by Harvard University Press, is his most recent book.

Hailed as a “profound, passionate, and wholly original celebration of Russian realism as both literary school and way of life,” by Boston University Professor Yuri Corrigan, the book came about almost by happenstance.

“An editor from Harvard Press dropped in on me a while back and said, ‘I have the book you were born to write,’” Morson recalled in an interview. “And I said, ‘Well, what do you mean?’ He said, “I want you to tell us the whole significance of the Russian literary-political-philosophical tradition and what we can learn from it. And it should be a big book of course.’

“I said I couldn’t do that because I’m not an expert in 20th century Soviet literature, my specialty is 19th century. He said, ‘That’s alright, we’ll give you time.’ That was seven or eight years ago,” Morson said, laughing.

In the “big book,” Morson tries to show “how Russian experience sheds light on the biggest questions of life,” he said. “Does life have a meaning? Is there really a difference between right and wrong, or is it simply whatever we say it is? All those big questions: The Russians explored them more profoundly than anyone else.”

A native New Yorker, Morson graduated from The Bronx High School of Science in 1965 and was planning to study physics at Yale University when “I fell in love with Russian literature.” He said it happened in stages over the course of his freshman and sophomore years, from the physical sciences to intellectual history to philosophy to philosophical novels ¬– stepwise the way Tolstoy and Chekhov wrote, moving along by small degrees – until he landed on Russian literature. He said physics painted “a beautiful picture of the universe” but the great Russian writers were more profound in their rendering of the great questions of life as played out in plot, character development and philosophical and psychological genius.

Morson spent a year at Oxford University and graduated from Yale in 1974 with his Ph.D. in Russian literature, which he taught for 12 years at the University of Pennsylvania before coming to Northwestern in 1986. He estimates since then he has taught more than 10,000 NU students.

A fast talker, brimming with ideas and excitement, Morson issues firm declarations about his academic passion. “Russia is the country with the greatest appreciation of literature in the world,” he told me. “Most people think literature reflects life. But Russians think the opposite: that life exists to be made into literature. Russians who posed the great moral questions didn’t write treatises, they wrote philosophical novels.”

In an article about Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, Morson wrote in a recent Commentary magazine article, “Dostoevsky himself suggested that at last the existence of the Russian people had been justified by its publication. It is hard to imagine a Frenchman or an American thinking his existence required justification, but, if he did, surely he would not find it in a work of literature!”

In the article Morson went on to say, “Literature is Russian scripture. The very phrase ‘Russian literature’ carries a sacred aura and resonates entirely differently from the way ‘American literature’ sounds to Americans.”

Maybe that’s because Russian novels explore such profound issues as good and evil, moral responsibility and freedom, as well as the role of theoretical ideas like anarchy, nihilism and Marxism-Leninism that drive fanatics and revolutionaries (the “certainty” of the book’s title) versus the more nuanced and powerful reality that the great Russian authors portrayed (“wonder”).

In a 2023 Northwestern Magazine article, “Lesson From Great Russian Novelists,” Morson wrote, “While 19th-century Russian revolutionaries and 20th-century Soviet officials were people of unfailing certainty, the great writers were people of wonder, marveling at a world of infinite complexity. For them, there were no final answers, but it was always important to deepen our understanding of the timeless questions.”

Some of the critical ideas the great Russian writers addressed, according to Morson, were:

Right and wrong: Almost all of Dostoevsky’s novels focus on the question of the role of morality in a universe governed by strict physical laws. “At the beginning of The Brothers Karamazov there’s a discussion of Ivan’s magazine article, which posits that if there is no god, all is permitted. This same issue is raised in Crime and Punishment, when Raskolnikov argues that if we live in a materialist universe, it’s hard to say where any morality comes from.”

These and the other classic Russian novels raise weighty questions, Morson said. “Do we want to accept that there’s no objective right and wrong, in which case what the Nazis and Soviets did was just another life choice? Or can we find a way in which right and wrong go beyond physical laws, something that constitutes an objective standard of good and evil.”

“In the 20th century, the Soviets brought these issues to life, declaring that with no god there was no right or wrong except what the party said.”

Crisis and catastrophe: “In most of the literature and drama we read, life is lived most authentically in moments of crisis and catastrophe. Tolstoy and Chekhov took the opposite view: what happens in crisis is largely the product of what happens in the hundred million ordinary moments of life, just more visible. But what really determines life – whether it’s good or bad – is how well we live the ordinary moments.”

Meaning and nothingness: “Does life have a meaning? A lot of people think the meaning is happiness. The Russians thought that was untrue. If you think the purpose of life is simply individual happiness, you will live a very shallow life. Because it’s the deepest things that make us happy and life worth living.”

Life and death: Tolstoy “was known in his lifetime as the poet of death,” Morson said, and cited the author’s novella The Death of Ivan Ilyich, “which many people believe is the greatest short novel ever written, one of the most profound surveys on how to look at death. The greatest scenes in War and Peace are the death of the hero Prince Andrei, which takes 100 pages. Tolstoy felt you can’t make sense of life unless you can make sense of death.”

Love and hate: War and Peace and Anna Karenina both have scenes where characters actually experience love for their enemies, Morson said. “Nobody had ever described Christian love that was psychologically convincing before Tolstoy. He traces the tiny steps the characters make to arrive at their epiphanies. But even though Christian love exists, in Tolstoy’s telling you realize it may not be such a good thing. He’s a realist!”

Asked about the great triumvirate of 19th century Russian writers, he said:

Lev Tolstoy “was the greatest realist of all time. He told this wonderful story about a painter named Bryullov, who was correcting one of his student’s sketches. The student said ‘You only touched it a tiny bit but it’s quite different.’ Bryullov replied, ‘Art begins where that tiny bit begins.’ Tolstoy said that’s strikingly true not only of art, but of life. Life is lived with tiny, tiny, brush strokes of consciousness taking place. To really describe people, that’s what you have to do. And that’s what he does, split second by split second.”

(As in Tolstoy’s novella, The Death of Ivan Ilyich: “How it happened it is impossible to say because it came about step by step, imperceptibly, but in the third month of Ivan Ilyich’s illness his wife, his daughter, his son, the servants, his acquaintances, the doctors and above all he himself were aware that the whole interest he had for other people was concentrated solely in this one thing – how soon he would vacate his place and at last release the living from the constraint of his presence and himself be released from his sufferings.”)

“And that’s how Tolstoy makes things totally convincing,” Morson continued. “He thought the difference between a great artist and a mediocre artist was not how much technical skill you have but how much you notice. So when he describes a painter in one of his novels, it’s the painter noticing things. When people praised the painter for his skill he’d think, ‘Really? I don’t have that much skill. If my cook could see what I can see, he could paint what I paint. But he doesn’t will himself to see.’ That’s what makes Tolstoy the supreme psychological realist.”

In the 2023 NU magazine article, Morson said that according to Tolstoy, “goodness really exists and is seen most often in the small acts of kindness available at every moment, and that people too often use great theories about life and society as an alibi to avoid taking individual responsibility.”

Fyodor Dostoevsky “was probably Russia’s second-greatest writer,” Morson said. “But he was interested in a different aspect of consciousness, interested in a character’s deepest motivations, the irrational subconscious that bubbles up. Freud was interested in the same thing, which was why Freud thought Dostoevsky was the greatest writer. Dostoevsky was interested in different things than Tolstoy – not the moment-to-moment play of consciousness. I think it depends what you’re interested in. But one of the two was the greatest psychologist who ever lived. It’s hard to pick.”

“If Russians were interested in human psychology,” Morson wrote in the Northwestern Magazine article, “they analyzed Dostoevsky’s characters. If they wanted to discuss life’s meaning, they might explicate Tolstoy’s novels.”

Anton Chekhov: “You’re going along in one of his stories. There’s a slight turn of perspective that you don’t notice right away,” Morson explained. “Pretty soon it becomes a different story. And maybe you have two stories layered over each other, sometimes even a third layer. And you never notice it. It seems very simple but what makes it disorienting is a shift in perspective. Let’s say a narrator switches to a different character’s point of view, and then another, at a point when it’s not obvious. The depth of the story comes from the combination of all these points of view.

“Other Russian writers have their big ideas and they often tend to focus on big philosophical and ideological issues. Chekhov was different, he was the great sceptic, the one who was never seduced by any political ideology or grand philosophy that attempts to explain everything. He’s almost unique among Russians that way. He’s the only one who never forgets that basic decency is more important than any philosophy.”

In the stories Happiness and Lights, Morson said, Chekhov explores “the meaning of life, and if so, is it happiness? But that’s rather a shallow view: You mean the whole universe exists so you can gratify yourself? Chekhov is always asking these questions, but he doesn’t answer them, he poses them in a much more profound way than we’ve considered them.”

Wonder Confronts Certainty also examines such 20th century Soviet literary giants as Alexander Solzhenitsyn (The Gulag Archipelago, “Arguably the 20th century’s greatest piece of nonfiction prose,” Morson wrote recently), In the First Circle, August 1914, November 1916 as well as his essays and speeches; Vasily Grossman (Life and Fate); Mikhail Bulgakov (The Master and Margarita); Varlam Shalamov (Kolyma Tales, in the translation by John Glad, “among the great works of 20th century literature,” Morson said); Boris Pasternak (Doctor Zhivago); Mikhail Sholokhov (And Quiet Flows the Don) and the short stories of Isaac Babel.

Asked which of his many books he is most proud of, he said, “Always the most recent one, of course. But of my earlier books there are two: Narrative and Freedom, my deepest book, about the human experience of time, examined through literature. And the book I had the most fun with and is the easiest to read for the non-specialist, The Words of Others, which explores famous quotations (like ‘Let them each cake’), famous witticisms, famous last words: are they accurate and what’s their role in culture.”

As to what’s next, Morson, 75, says he has no plans to retire. He continues to teach his popular Survey of Russian Literature classes on The Brothers Karamazov, Anna Karenina and War and Peace, and writes book reviews and other articles for popular magazines and newspapers, such as this recent piece in the Wall Street Journal on the 50th anniversary of the publication of The Gulag Archipelago.

“The fact is, I’m still having fun with it,” he explained.

+ There are no comments

Add yours